Il presente contributo – che riprende ed amplia una relazione tenuta ad un convegno internazionale – analizza il rapporto tra forma di governo e lobbies nell’ordinamento della Gran Bretagna ed in quello composito dell’Unione Europea. L’analisi evidenzia come vi sia una stretta connessione tra la forma di governo di questi ordinamenti e il modello regolatorio del rapporto tra decisori pubblici e portatori di interessi. In tal senso sono stati individuati due modelli contrapposti: quello della regolazione-trasparenza (basato su un insieme di norme finalizzate a rendere trasparente il processo decisionale), e quello della regolazione-partecipazione (basato su norme finalizzate non solo a rendere trasparente il processo decisionale ma anche ad assicurare la partecipazione delle lobbies al processo decisionale). In questo contesto, emerge il sistema italiano caratterizzato da una normativa frastagliata e, per così dire, “strisciante”, con un “andamento schizofrenico”.

1. Lobbies, Pressure Groups and Parliaments

“Interest Group”, “Lobbying”, “Pressure Group”, in the common use, we often hear these keywords used as synonyms or interchangeably. But distinctions are important, particularly in this case, and not just under a terminological point of view, but even from a conceptual one. Moving from this clarification is important for any kind of reflection on lobbying, especially under the constitutional lens adopted for the present paper.

“Interest Group” is a group of people who share the same aim and pursues certain claims towards other groups. In this case, the substantive “interest” assumes a clear connotation just when it is blended with an adjective: “private”, “public”, “social”, “religious”, “local” etc. Therefore it is the adjective who describes the nature and the range of the group (Mattina, 2010).

“Pressure Group” is an interest group that dialogues with public decision-makers in order to influence the legislative process and to obtain advantages or to prevent disadvantages (not just economical). There is thus a very relevant difference between the two Groups which consist on the object of their pressure activities.

The legal activity of persuasion to the public decision-maker can be defined “Lobbying”. It is an expression that has its root in the far past (see The Oxford Universal Dictionary, p. 1228) as low as the Latin times of “labia” (1553) indicating the space inside catholic monasteries, where priests used to meet and talk with each other. The word entered into the political vocabulary in 1600, referring the wide room at the entrance of the House of Commons. A place where MPs, journalists and lobbyists used to make conversation. It was in 1832 that “to lobby” became a verb, meaning the persuasion activity exercised by the lobby agents towards politics in Campidoglio, the meeting place of the United States Congress. During the Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant, after the Civil war, “lobbying” has became a consolidate concept in the American political context. President himself used to meet people in a specific area of the Willard Hotel, enjoying a good cigar and drinking brandy.

But why and when the Western society needed lobbyists? It’s not an easy question, but we can affirm that it occurred during the development of Industrial democracies, and in particular through the transformation of the State – notably from Liberal to “Social State” – lobbies emerged. Within the “Mercantile State” (Shumpeter) where State directs and guides public policies and where the citizens needs became larger, lobbies has represented a sort of natural phenomenon. The general interest thus become the result of a negotiation process between different stakeholders, and it’s not any more considered “an expression of the general will” (Article 6 of the Declaration of the Rights of Man an the Citizen, 1789) under the ancient vision of Rousseau that culminated with the so called Law “Le Chapelier” (1791), that banned the intermediate bodies and any kind of other interpreters between Parliament and citizens.

This point of view, that can be described as a model of “Jacobin” Constitutionalism, is opposite to the “Anglo-Saxon” Constitutionalism one, where the general interest doesn’t pre-exist as a sort of abstract entity but it is instead the result of a consultation and negotiation process at the end of which the politician is responsible in front of citizens (accountability).

Lobbies are part of the democratic system such as political parties, operating in the space between citizens and public Institutions, relating with political actors, trade unions and local authorities. Due to the interaction among different groups, political decisions truly representative can be taken (Ekstein H., 1963, p. 191). So which are the differences between political parties and lobbies? First of all, let’s say that the latters follow their private interests, without assuming any responsibility in performing public faculties. Political parties are “open”, lobbies are not as private and “closed” association. A lobbyist doesn’t want to manage political power, rather to have preferential access to that power in order to exercise his influence. Instead a politician wants to be a legislator, a public decision-maker and the political elections are the only way to reach his goal, in fact “political parties, which can be seen as collection of interest groups, seek to direct the energies of groups and movements through the electoral process to win control of government in order to implement a broad–based political platform” (Thomas C. S., 2001, p. 7).

2. Form of Government and lobbies: a general introduction

Lobbies have a direct “influence” on the Form of government, because they play a role in the relationship between the bodies involved in addressing the political system, so “in order to understand pressure groups, one needs to look not just at the behavior of the groups but also at the behavior of government” (Grant W., 1989, p. 17). Studies on the regulation of pressure groups – at the same way of studies on political parties – constitute “an essential element of the bourgeois society” and they “certainly belong, as object of the scientific research, to the Constitutional law” (Mangiameli S., 1993, p. 140 author’s translation). In the light of these considerations, we can also operate some generalizations and distinctions related to the different Form of government involved.

1) Form of government where Political parties are able to understand social interests and to represent them in Parliament, having a strong and influential structure that filters different interests even if some interests cannot be represented (i.e. because there is an electoral system that “cuts off” some parties from the Parliament). In this contest, regulations have to make transparent the relationship between parties, Parliament and lobbies. And not to guarantee participation of lobbies, because major part of interests are already represented by political parties. We can conventionally describe it as “Interest-transparent” Form of government.

2) Form of government where Political parties are unable to represent social interests because there is a crisis of their legitimacy, or they have a weak structure, or they exist only during the electoral campaign. Public bureaucracies have an unspecific education (generically trained) and only the lobbies can represent different interests. In this context, regulations have to guarantee not only the transparency of the process but also the participation of lobbies to the public decision process. So bureaucracies have specific information, especially technical, politicians understand the concrete interests of the community, and the public decision process has the right legitimacy. In this case we are in the “Interest-guaranteed” Form of government.

Assuming that Pressure group are part of democratic process, the “rules of the game” within the lobbyist and the decision makers are placed become fundamentals in order to guarantee an effective and general representation of the interests. So “to assert that the organization and activity of powerful interest groups constitutes a threat to representative government without measuring their reaction to and effects upon the widespread potential groups (unorganized interests) is to generalize from insufficient data and upon an incomplete conception of the political process” (Truman D., 1951, pp. 515-516).

The point become not “if” lobbies exist, but “how they participate” in the political process. And “how” can be related to several aspects: for example, which kind of relationship is it possible between lobbies and public decision makers? Who are the “public decision makers”? How to distinguish different lobbies (economic, non-profit, social…)? How to guarantee the transparency of the process and a fair participation of every lobby? The analysis of lobbying (subjects and activities) can be approached in different ways, and many other questions are related to the theme, like the cost of lobbying or its impact on the society. These interesting aspects, ranging from sociology, through politology, to more properly economic considerations, are not strictly related to the Constitutional law profile. But herein it must be pointed out the multifaceted considerations which can be related to the lobbying studies, which represent a further fascinating element of this research’s theme.

3. Form of Government and models of regulation of lobbying

In order to clarify the legislative negotiation’s aspects, States tried to regulate the (existing) relationship between lobbies and public decision-makers through the regulation of two aspects: (1) the first is addressed to the public decision-makers, and concerns “Internal” rules; (2) the second is addressed to the lobbyists, and regards “External” rules. Related to them, different issues have been considered like, respectively, (1) rules governing the legislative procedure, codes of conduct and codes for parliamentarians, rules governing the constitution of Inter-parliamentary groups; (2) rules for lobbyists and for the private financing of politics.

On these basis, two regulations “models” of lobbying can be identified: (a) Transparency, (b) Participation (Petrillo, 2011).

3.1 The Transparency model: the UK case

In such a case, the aim of regulation is to guarantee the transparency of the public decision process, and to disclosure the reasons behind the adoption of a law and of the people who influenced it. Regulations try to make the process transparent, and not to engage stakeholders in the decision process. A metaphor can help to see the effects of the “transparency regulation”, imaging a room with “crystal walls” where decisions are taken. Inside the room, there are decision makers. Outside, lobbyists, citizens and anyone can see what happens inside, those who participate in the legislative process and what they says. Sometimes, it happens that someone from outside can be invited, as stakeholder, to get in and say what he thinks about the matter. Everything happens under the eyes of people outside. Canada and United Kingdom regulations correspond to this model.

“The practice of lobbying in order to influence political decision is a legitimate and necessary part of the democratic process” (House of Commons, 2009). Starting from this consideration, we can easily understand the way London has ruled the relationship between Parliament and lobbies, which is strictly related to factors as the electoral system or the relation between electorate and public decision-maker. Today, there is still a lack of an organic discipline on the Pressure groups, but there are different rules operating on the both side that can be classified under the above mentioned “Internal” or “External” distinction.

Regarding the exam of the most relevant “Internal” rules, we can start from 1839, when the Speaker of the House of Commons introduced the duty for parliamentarians to declare any kind of conflict of interests beyond the theme under discussion in Parliament. That practice has been integrated in 1830 with the approval of a motion stating that “it is contrary to the law and usage of Parliament that any Member of this House should be permitted to engage, either by himself or any partner, in the management of private bills before this or the other House of Parliament, for a pecuniary reward” (House of Commons, meeting of 26 February, 1830).

But it was just in 1974, that all the practices related to lobbying have been formalized under the impulse of the motions proposed by the Speaker of the House of Commons, Edward Short. In particular, it must be underlined the establishment of a permanent Selected Committee on Members’ Interests and the institution of a Register of the parliamentarians interests – extended since 1996 to the House of Lords (online since 2008) – where they had to declare any business, social or cultural interest and (since 1985) the specific interests of any members of their staff. In 1994, Prime minister John Major created a special commission called Committee on Standards in Public Life, chaired by the Hon. Nolan, with the aim of examine current concerns about standards of conduct of all holders of public office, including arrangements relating to financial and commercial activities, and make recommendations which might be required to censure the highest standards of probity in public life. The mentioned Committee didn’t proposed a Register of lobbies and either to modify the existing Register of Parliamentarians interest, but recommended to forbid (and monitoring) MPs to receive money for “consultancy” activities coming from lobbies.

In November 1995, embracing the recommendations of Hon. Nolan’s Committee, th

e House of Commons established the Parliamentary Commission for Standards and approved the first Code of Conduct for Deputies, which has been modified in 1996 and (last) 2009.The choose of the code of conduct represents a significant elements of the Britain contest, as it has been stated “self-regulation can be a more effective device for controlling activity than externally imposed regulation […] A self-regulating body derives status, respect and self-respect from the fact it is trusted to regulate itself” (Oliver D., 1997, p. 539). After the lobbygate of 1998, which involved a former special advisor of Prime minister Tony Blair (Mr. Derek Draper promised to organize under payment a meeting between a multinational company and a Minister of Blair’s Government; see Cash for access: £2000 buys a Minister, in The Observer, 19 July 1998) a Guidance for Civil Servants has been introduced aimed to rule the contacts between lobbyists and Public officer, recording all the meetings held. One year later, the Cabinet Secretary Sir Richard Wilson, has extended the mentioned Guidance to the Ministers.

Considering the “External” rules, since 1837, many initiatives by both the Speakers has been implemented in the define most of all the procedures to follow for the presentation and the approval of the private bills. In 1860, the House of Commons’ Rules has been modified including the “parliamentary agent”, which has been described as a figure who wants to keep stable and directs contacts with parliamentarians and their staff, in order to influence the decision making process sending to them documents, researches, position papers and, also, draft bills. These agents are obligate to enter their names on a public register, including a “certificate of honorability” released by an MPs or by a great renown lawyer (on the theme Erskine-May, 2005, p. 939).

Considering the Register’s outdatedness of the above mentioned Register – the “parliamentary agent” in fact is a figure antiquated owing to the past (there are just few agents accredited today) – the Public Administration Committee of the House of Commons have prepared a report (House of Commons, 2008) recommending the creation of a Register of lobbyists by the main organizations representing lobbyists in United Kingdom, notably the Association of Professional Political Consultants (APPS), the Chartered Institute of Public Relations (CIPR) and the Public Relations Consultants Association (PRCA). In 2010, these organizations have created an independent organism, the UK Public Affairs Council (UKPAC) which has been in charge of managing a Public Register of lobbyists. The Register represents today a relevant source of information and a symbol of transparency together with an instrument of auto-regulation. The UKPAC is still working on a Code of conduct for the lobbyist which should be available within the next months.

In respect the financing of politics, the (2009) Political Parties and Elections Act represented a turning point in the discipline. That’s because the new regulations introduced the principle of the transparency, rather than limiting the private financing: “under the current legal framework for funding of political parties, there is no limit on the level of donations that individuals or organizations may donate. The Government will pursue a detailed agreement on limiting donations and reforming party funding in order to remove big money from politics” (Prime minister during The Queen’s Speech, House of Commons, 25 May 2010).

In conclusion, it can be observed that British legislator doesn’t have the perception of lobbies as external and estrange elements to the Parliament. That’s why there is a “minimal” framework regulation which is addressed more to the internal side (MPs) than external ones (lobbies) as long as for the firsts there are important considerations in term of accountability. That said, the lobbyist is certainly recognized as an interlocutor of politicians, but he has not the right to participate to the decision making process. The process tends to be transparent: names of lobbyists, interests involved and reasons behind a decision are known.

3.2 The Participation model: the EU case

Aim of this model is not just to guarantee the transparency of the decision making process, but also to ensure the participation of stakeholders to such a process. Following the previous metaphor, we can now imagine the same decision room with “crystal walls”, but in this case there is also the right for the lobbyist to enter in this crystal room participating in the discussion. In accordance with the regulation, in fact, he can sit down around the table, cooperating in the decision making process and, of course, under the eyes of the outsiders. This right of participation is based on the necessity of public decision-makers to understand social interests that parties cannot represent. Example of this kind of model are the USA and the EU system.

EU lobbies activity increased in the 1990s, as a result of the gradual transfer of regulatory functions from Member States to the EU institutions, and the concurrent introduction of qualified majority. In parallel with this increasing functional supply, institutional demand for EU interest groups activity was facilitated by the openness of the European Commission and European Parliament.

Lobbies in Brussels were progressively able to exert influence along the European policy process from initiation and ratification of policy at the Council of Ministers, setting of the agenda and formulation at European Commission led forums, reformulation of policy at the European Parliament committees, to the final interpretation, harmonization and implementation of regulation in the national state. Following and accessing every passage of the policy process, EU interest groups become an important supply of information on the development and knowledge of EU public policies and a potential source of legitimacy for policy-makers (Lupo, Fasone 2012, pp. 37 ss.). Today, there are no less that 15000 lobbyists working around them European institutions and that’s where “Brussels DC” (referring Washington DC) comes from.

“Political systems need legitimacy from their subjects in order to undertake a full range of governance functions. Legitimacy arises from two sources: inputs (the ability to participate in political decision making) and effectiveness (results). The limited nature of the EU as a political regime can partly be explained through its lack of input legitimacy”. Because of this lack, continues the author, the EU is an ideal venue for interest groups which have very positive meaning, in fact “they bring much needed resources to policy making, implementation, and monitoring in some accounts of how European integration develops, they help the EU to acquire more policy competencies by bringing irresistible demands to member state doorsteps, and assist in the popular identification with the European Union”(Greenwood J., 2004, p. 146). Interest groups are under this light not only helpful in policy making, but also in making the EU closer to citizens. Is not a coincidence some authors consider the involvement of lobbies in the Brussels decision making process a way to reduce the “democratic deficit” that characterizes the European institutions (Santonastaso D., 2004) .

The entry into force (2009) of the Treaty of Lisbon has given to citizens, group of interests and associations a central role in the definition of the European policies. In the first place as provided in Article 10 of the Treaty on European Union: “Every citizen shall have the right to participate in the democratic life of the Union. Decisions shall be taken as openly and as closely as possible to the citizen”. The implications are not just in terms of “subsidiarity”, but also in generating a proper “opening” of the decision making-process to the instances of community, as it has been formalized in Article 11 “The institutions shall, by appropriate means, give citizens and representative associations the opportunity to make known and publicly exchange their views in all areas of Union action”. Within this framework “the institutions shall maintain an open, transparent and regular dialogue with representative associations and civil society”, confirmed also by the role of the European Commission in carrying out “broad consultations” with parties concerned in order to ensure that the Union’s actions are “coherent and transparent” (The Treaty on European Union, Article 10 (3); Article 11).

3.2.1. Lobbying and the European Commission

Until may 2005, at the Commission level, lobbies always operated through participation, more or less informally and more or less in transparency, in Expert Groups that compose several (1000 or more?) technical committees of the Commission. In this context, lobbies used to participate to decision making process, but outside any rule and with a lack of transparency. In 1993 the Commission invited lobbyists (COM1993, C1666/04) to adopt their own code of conduct on the basis of minimum criteria proposed, like: acting in an honest manner always declaring the interest they represent; not disseminate misleading information; not offer any form of inducement in order to obtain information or to receive preferential treatment. This self-regulation system encouraged by the Commission has been followed by various organization of European public affairs (consultants and consultancy firms), which have adopted a voluntary code of conduct based on these minimum standards proposed by Brussels.

In 2005, the Commissioner against fraud, Jim Kallas, stressing the importance of a “high level of transparency”, ensuring that the Union is “open to public scrutiny and accountable for its work”, launched the European Transparency Initiative (ETI). The project intended to work on a series of transparency-related measure proposed by the Commission in the White Paper on European Governance (COM2001, 428) in terms of access to documents; launching of database providing information about consultative bodies and expert groups advising the Commission; proposing a wide consultation of stakeholders in giving a contribution to implement the Commission’s “better lawmaking” policy. This public consultation has been opened in 2006 on the base of a Green Paper on European Transparency Initiative (COM2006, 194).“It is a combination of rules enforcing supervision and a broad commitment to the values underpinning the rules that amounts to a credible system”, explained Kallas adding that “because there is nothing wrong with lobbying, there should be nothing to hide” (Kallas S., 2006). The initiative proposed three objectives: (i) made more transparent the decision making process for the allocation of European funds; (ii) revise the public officials’ Ethical code and the rules for the European documents’ consultation; (iii) define an organic and common normative framework regarding the relations between European institutions and lobbies.

In the Green Paper, we can see for the first time a definition of “lobbying”, meaning all the activities carried out with the scope of influencing the policy formulation and decision-making process of the European institutions. Accordingly, “lobbyists” are defined as persons carrying out such activities, working in a variety of organizations such as public affairs consultancies, law firms, NGOs, think-tanks, corporate lobby units (“in-house representatives”) or trade associations. Lobbying become a legitimate part of the democratic system, recognized as tool for bringing important issue to the attention of the European institutions. At the same time, undue influence should not be exercised on European institutions and when lobby groups seek to contribute to EU policy development, it must be clear to the general public “which input” they provide to the European decision-makers. For this reason the Green Paper proposed: (i) a voluntary registration system run by the Commission with clear incentives for lobbyists to register; (ii) a common code of conduct for all lobbyists or at least common minimum requirements; (iii) a system of monitoring and sanctions to be applied in case of incorrect registration and/or breach of the code of conduct.

European Commission committed itself to launch the new Register of lobbyist (on a voluntary basis), improving the general transparency through a better application of the rules on the consultation process and reorganizing correspondent the web site. Respecting the deadlines announced, the 27th of May 2008 the European Commission launched the Register of lobbyists providing a general overview, open for public scrutiny, of groups engaged in lobbying the Commission. All entities engaged in activities carried out with the objective of influencing the policy formulation and decision-making processes of European institutions are expected to register. These activities include: contacting members or officials of the EU institutions, preparing, circulating and communicating letters, information material or argumentation and position papers, organizing events, meetings or promotional activities (in the offices or in other venues) in support of an objective of interest representation. Registration does not constitute accreditation and does not entail access to any privileged information and financial disclosure requirements. So, why a lobbyist should register himself? A European Commission explained, that groups and lobbyists which are registered would be given an opportunity to indicate their specific interest and, in return, would be alerted to consultations in those specific areas. So, only lobbyists who are in the register would be automatically alerted by the Commission.

3.2.2. Lobbying and the European Parliament

The Parliament was the first European institution to address the phenomenon of an increasing number of interest groups at European level and especially the consequences of this evolution for the legislative process. In July 1996, the European Parliament approved a modification of Article 9 of the Rules of Procedures and introduced Annexes I and IX with some consistent modifications in term of lobbying (Lupo, Fasone, 2012, pp. 37 and follows).

Regarding the “Internal” rules, it must be underlined the Code of conduct for parliamentarians, which included first of all the obligation to make public their own interests. The MPs must record any professional activities, function or paid activity, declaring before the correspondent public debate any eventual interests linked with the theme which will be discussed. The code is valid both for parliamentarians and for members of their staff. It is also included the prohibition to accept gifts and advantages directly motivated to their charge. Duty to declare any gift or earning in any form. The register has to be updated constantly and any year, otherwise there is a system of sanctions which can reach up to the suspension of the parliamentarian.

A further interesting issue in terms of lobbying is the Intergroups which are subject to internal rules adopted by the Conference of Presidents on December 16, 1999 (last updated on February 14, 2008), which set out the conditions under the Intergroups may be established at the beginning of each parliamentary term and their operating rules. Intergroups can be formed of Members from any political group and any committee, with a view to holding informal exchanges of views on particular subjects and promoting contact between Members and civil society: Intergroups are not Parliament bodies and therefore may not express Parliament’s opinion. Nevertheless, Intergroup undoubtedly represents a lobbying instrument and that’s why the above mentioned internal rules disposed that Chairs of Intergroups are required to declare any support they receive in cash or kind, according to the same criteria applicable to Members as individuals. The declarations must be updated every year and are filed in a public register held by the Quaestors. Today (November 2012) there are 27 Intergroups inscribed, from the Sustainable Hunting, Biodiversity Countryside Activities and Forest one, to the Ways of Caminos de Santiago or the Anti-Racism & Diversity one.

Regarding the “External” rules, the Article 9 of the mentioned Rules of Procedures (nota) disposes that the “long term visitors” of the European Parliament must be recorder on a Public register, declaring all information in terms of persona data, company or organization represented, interests involved and name of parliamentarians which could offer guarantees or references on the applicant. The “long term visitor” received a badge in order to enter and to be recognized in the European Parliament buildings, he is informed on the activity of the Permanent Commissions and has the unofficial right to be heard in the Commissions. The register of accredited lobbyist has been published (since 2003) on the EP website, but in a form of an alphabetical list providing only the names of the badge holders and of the organization they represent: it gives no indication of the interest for which a lobbyist is acting. On the other side, he respects a Code of conduct which includes disposition in order to guarantee the widest transparency in his relations with the parliamentarians, with the obligation to always declare the interest represented and not to dispose official documents received in the European Parliament. This is the case of a “minimal” model of regulation, with the disposition of just few rules aimed to permit lobbying in general framework of transparency. But there is an important weakness which must be underlined, consisting in the rules’ lack of a definition of “lobbying”.

In order to solve this contradiction, the European Parliament adopted, on May 8, 2008 (547 votes to 24 and 59 abstentions) a Resolution on the development of the framework for the activities of interest representatives (lobbyists) in the European institutions. The European Parliament “recognizes the influence of lobby group on EU decision-making process and therefore considers it essential that Members of Parliament should know the identity of the organizations represented by lobby groups” and, at the same time “emphasizes that equal access to all the EU institutions is an absolute prerequisite for the Union’s legitimacy and trust among its citizens”, considering the importance for the civil society to have free access to the European institution, “first and foremost to the Parliament”

(Hon. Ingo Friedrich, Rapporteur for the Constitutional Affairs Commission, Act No. A6-0105/2008, European Parliament, May 8, 2008).

In order to achieve these goals, EP proposes a reflection on four elements: (i)“Legislative footprint“ (it means to record the lobbyists’ positions over any single draft legislative proposals); (ii) Definition of lobbying; (ii) Mandatory and not voluntary register (different from the Commission one); (iv) Common Register and rules.

The EU Transparency Register

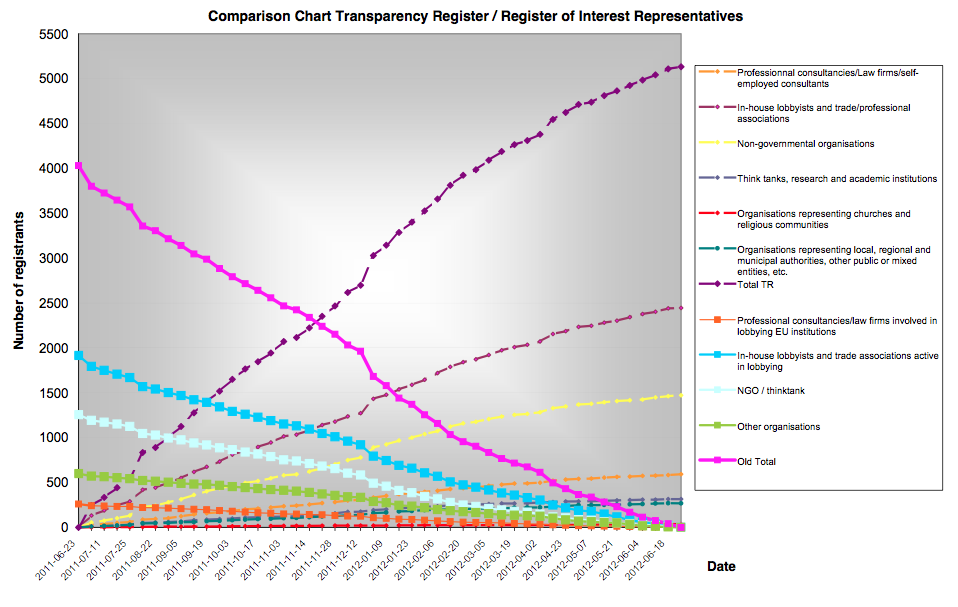

On 23 June 2011, the European Parliament and the Commission concluded an Interinstitutional Agreement (OJL191, 22.7.2011) laying down the rules on the establishment of a Common Register for the registration and monitoring of organizations and self-employed individuals engaged in EU policy-making and policy implementation. The new registration system has been built upon the register launched by the European Parliament in 1996 and the European Commission ones launched in 2008. The European and the Council has been also invited to join the register and, more generally, all EU institutions, bodies, agencies has been encouraged to use this system themselves as a reference instrument for their own interaction with organizations and self-employed individuals engaged in EU policy-making and policy implementation.

It’s a web-based voluntary registration system with incentives for interest representatives to register (including automatic alerts of public consultations on issues of known interest to the registered organisms), available on-line to everyone. Registrants need to subscribe to the Code of Conduct; providing some information: (i) general and basic information (organization name, address, e-mail address, identity of the person legally responsible and organization’s director, goals, fields of interest, activities, country); (ii) number of persons involved in activities included in the scope of the register; (iii) names of the persons for whom badges affording access to the European Parliament’s buildings; (iv) main legislative proposals covered in the preceding year by activities falling within the scope of the transparency register; (v) contact person responsible for the relations with the administration of the register; (vi) financial information referring to the most recent financial year closed.

In their relations with the EU institutions and their Members, officials and other staff, registrants (lobbyists) shall always identify themselves and the work represented declaring interests and aims promoted and specifying the clients or members whom they represent. Lobbyists cannot obtain or try to obtain information dishonestly, or by use of undue pressure or inappropriate behaviour and not claim any formal relationship with the EU or any of its institutions in their dealings with third parties, nor misrepresent the effect of registration in such a way as to mislead third parties or officials or other staff of the EU. Those aspects are very important in the lights of the recent resignations of EU Health Commissioner, John Dalli, in a dispute on tobacco lobbying (See http://euobserver.com/institutional/117895).

Registrants are not allowed to sell to third parties copies of documents obtained from any EU institution; not to induce Members of the EU institutions, officials or other staff of the EU, or assistants or trainees of those Members, to contravene the rules and standards of behaviour applicable to them; to observe any rules laid down on the rights and responsibilities of former Members of the European Parliament and the European Commission. In this respect, it must be underlined that “revolving door” represents still an unsolved and very discussed issue in Brussels) nota http://corporateeurope.org/pressreleases/2012/ombudsman-complaint-commission-failure-curb-revolving-doors). Individuals representing or working for entities which have registered with the European Parliament receive a personal, non-transferable badge affording access to European Parliament.

The Transparency Register is run by a Joint Transparency Register Secretariat (JTRS) made up of officials from the European Parliament and the European Commission, operating under the coordination of a Head of Unit in the General Secretariat of the Commission and undertakes the following tasks: help desk for internal and external users; preparation and regular update of the content on the Transparency Register web site; quality checks of the information provided by registrants and handling of complaints; communication and awareness-raising among internal and external users; elaboration of the annual report and preparation for the political review; gathering information on the practice of lobbying and how it is regulated in EU Member States and in certain third countries.

Complains way be submitted by completing a standard form on the website of the register, specifying one or more clauses of the code of conduct which the complainant alleges have been breached (maximum 4000 characters) and providing documents or other materials to support their complaint. In this case, the JTRS shall verify that sufficient evidence is adduced to support the complaint. On the basis of such verification, it decides the admissibility and, if admissible, registers the complain and establish a deadline (20 working days) for the decision on the validity of the complaint and than it starts a further investigate phase. The Joint Transparency Register Secretariat shall inform the registrant in writing of the complaint made against that registrant and the content of the complaint, and shall invite the registrant to present explanations, arguments or other elements of defence within 10 working days. If the complaint is upheld, the registrant way be temporarily suspended from the register pending the taking of steps to address the problem or may be subject to measures ranging from long-term suspension to removal from the register.

The scope of the register covers all activities carried out with the objective of “directly or indirectly” influencing the formulation or implementation of policy and the decision-making processes of the EU institutions and the decision-making process of the EU institutions, irrespective of the channel or medium of communication used, for example outsourcing, media, contracts with professional intermediaries, think-tanks, platforms, forums, campaigns and grassroots initiatives. These activities include, inter alia, contacting Members, officials or other staff of the EU institutions, preparing, circulating and communicating letters, information material or discussion papers and position papers, and organizing events, meetings or promotional activities and social events or conferences, invitations to which have been sent to Members, officials or other staff of the EU institutions. Voluntary contributions and participation in formal consultations on envisaged EU legislative or other legal acts and other open consultations are also included, “all organizations and self-employed individuals, irrespective of their legal status, engaged in activities falling within the scope of the register are expected to register” (OJL191, 22.7.2011, p. 1).

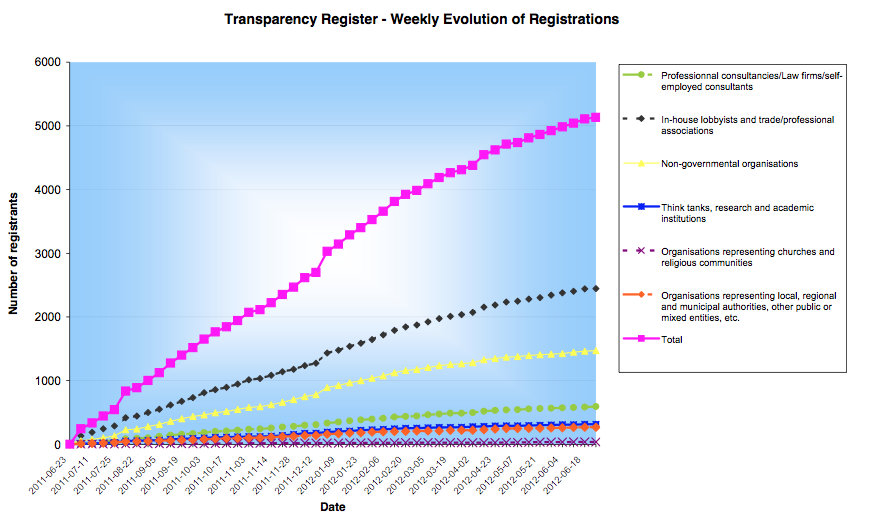

By 5 November 2012, a total of 5.463 individuals and organizations were enrolled in the Transparency Register, including 622 professional consultancies and 42 law firms, 1,530 trade/ professional associations, 747 companies, 1.550 NGOs, 380 think tanks and research and academic institutions, 112 academic institutions, 131 organizations representing local, regional and municipal authorities. Churches and religious communities, political parties, local, regional and municipal authorities are not concerned by the register, but their representative offices, legal entities or any organization created to represent them in their dealings with the EU institutions are expected to register.

Source: www.europa.eu

Other activities are excluded: (i) activities of legal and other professional advice, when they relate to the exercise of the fundamental right to a fair trial of a client, including the right of the defence in administrative proceedings; (ii) activities of the social partners when they are part of the Social Dialogue. This applies mutatis mutandis to any entity specifically designated in the Treaties to play an institutional role; (iii) Activities in response to direct and individual request from EU institutions or Members of the European Parliament such as ad hoc or regular requests for factual information, data or expertise and/or individualized invitations to attend public hearings or to participate in the workings of consultative committees or in any similar forum.

4. At the end: the snake model of the Italian regulation

In Italy there is not a systematic regulation of lobbying activities (Lupo, 2006), due likely to historical and political reasons (such as respectively the French influence and the role of political parties as exclusive mediators – cfr. Morlino, 1991). Another reason can be found in a sort of “embarrassment” to admit that “the King is nude” (Frosini, 2000, p. 228) or, in other words, that parties are able no more to represent social interests.

Nonetheless, there is a silent regulation, grovelling as a snake: scattered norms establishing duties, faculties, functions to lobbies ad providing their participation to the decision making process (Petrillo, 2011, pp. 297 ss.).

This is true both regarding Government and Parliament.

The most interesting phase in terms of lobbying is the preliminary examination of bills. In this respect, we can see the Article 79 of the Rules of Procedures (Chamber of Deputies), when states that the Permanent Commissions should verify the necessity of legislative intervention, the coherence with the Constitution and with the EU regulations, the proper specification of the objectives and of the instruments to achieve them. The Permanent Commissions should also analyze the costs and benefits for citizens, enterprises, public administrations and the quality and clearness of the legislative text; for these scopes, during the preliminary examination of bills the Commission establish hearings or ask for documental contributions. The problem of these instruments it is their use often “off record”, which for sure runs against transparency. In addition, hearings are decided by the Presidents of permanent Commissions, without any guaranty for the fair participation of every interest group.

But these examination of bills, with theoretical participation of lobbies, is cancelled by a standard procedure establish by the Government and accepted by the Parliament. In fact the Government can present a maxi-amendments to every bill with the request of the vote of confidence. In this way, the Government prevents any control on the text and on its origin, and makes useless all the preliminary analysis of the bill by the Parliament (including hearings attended by interest groups).

In conclusion, these snake-rules are schizophrenic, because the legislator, that establishes them, denies them at the same time: preliminary examination become useless by maxi-amendments of the Government; impact analysis of regulation (AIR) is only used as a sterile practice, etc. In this contest, lobbies operate in a total obscurity. Corruption could be a natural consequence.

The pre-legislative step of its bill proposals is the result, at ministerial level, of informal consultations with interest groups. Each Minister that presents a bill, has also to submit a report concerning the impact analysis of regulation (AIR). The former consists in the preventive evaluation of the effects of regulation on citizens, enterprises and on the functioning of public administrations, through the comparison of alternative options: for these reasons the involvement of interest groups, should be crucial, because only in this way the Government understand the impact of the proposal bill on the community. Unluckily, both the reports are (almost) always insufficient and lacking of any information, filled in only to accomplish procedural requirements (Celotto, 2004, pp. 56 ss.).

Is the time changed? The Ministry of Agricultural, Food and Forestry Policies, in fact, has established an “Unity for Transparency”. As stated by the Minister’s Decree No. 2319 of February 9, 2012, the Unit shall be headed by the Chief Cabinet and is composed of experts who will carry out this task free of charge. Primary task of the Unit is to treat the consultation procedures required by law, the agro-food industry lobbyists during the preparation of draft laws and relations which are under ministerial competence (is this a change for the Italian democracies?- Morlino, 2011).

To this end, lobbyists who wish to participate in these consultations are required to be registered on a public list (“List of people carrying particular interests). The list, like all documents produced by the lobbies, will be available to anyone on the website of the Ministry. In this list the holders of interests shall specify: (i) the data and the business address of the holder or holders of particular interests, and any additional professional activities carried out; (ii) the identity of the employer, or the identification data of the customer; (iv) the interest or interests that are represented; (v) the financial and human resources that you have for the conduct of representation and lobbying activities.

The registered parties may also submit additional proposals, studies, documents, research to the Unit for Transparency in order to represent their legitimate interests. There is the obligation for registered subjects to submit (by July 30 of each year) a summary report of the activity. In case of non-submission of the report, the subject will be deleted and cannot participate in the consultations. The Minister of Agriculture, Food and Forestry report annually to Parliament, as part of a more general report on the implementation of regulatory impact analysis; on the implementation of the above lobbying decree and on the activity of lobbying put in place towards the above mentioned Ministry.

Bibliography

Bouwen, P., and M. McCown, Lobbying versus Litigation: Political and Legal Strategies of Interest Representation in the European Union, in Journal of European Public Policy 14, 3, 2007.

Broscheid, A., and D. Coen, Lobbying Activity and Fora Creation in the EU, in Journal of European Public Policy 14, 3, 2007.

Beyers, J., and B. Kerremans, Critical Resource Dependencies and the Europeanization of Domestic Interest Groups, in Journal of European Public Policy 14, 3, 2007.

Celotto A., La consultazione dei destinatari delle norme, in Studi parlamentari e di politica costituzionale, 1, 2004, pp. 56 ss. .

Coen, D., Business Lobbying in the EU, in Coen D. and Richardson, Lobbying the European Union, Institutions, Actor and Policy Oxford University Press, 2008.

European Commission, Communication on Transparency in the Community, COM (1993) C1666/04, 1993.

European Commission , White paper on European Governance, COM (2001) 428, 2001.

European Commission, Green paper on European Transparency Initiative. COM (2006) 194, 2006.

European Commission and European Parliament, Agreement between the European Parliament and the European Commission on the establishment of a transparency register for organizations and self-employed individuals engaged in EU policy-making and policy implementation, OJ L 191, 22.7.2011, 2011.

Ekstein H., Group Theory and Comparative Study of Pressure Groups, in Ekstein H., Apter D. E., Comparative Politics. A Reader, Free Press, New York 1963.

Frosini T. E., Gruppi di pressione, in M. Anis (curator), Dizionario Costituzionale, Laterza, 2000.

Greenwood J., The research for input legitimacy through organized civil society in the EU, in Transnational Association, 2, 2004, pp. 145 and follows.

Greenwood, J., Interest Representation in the European Union. Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

Grant W., Pressure groups, Politics and Democracy in Britain, Philip Allan, 1989.

Kallas S., Mr Smith goes to Brussels, in The Wall Street Journal Europe, 6 February 2006.

Mangiameli S., Gli interessi organizzati tra fenomenologia sociale e costituzionale – Introduction to Kaiser J.H., La rappresentanza degli interessi organizzati, Giuffrè, 1993.

House of Commons (UK), Report: Lobbying: Access and Influence in Whitehall, Public Administration Selected Committee, HC 36-1, January 2008.

House of Commons (UK), Treatise on Law, Privileges, proceedings and Usage of Parliament, XXIII Ed., London, 2005.

Lupo N., Verso una regolamentazione del lobbying anche in Italia? Osservazioni preliminari, in www.amministrazioneincammino.luiss.it, 2006.

Lupo N., Fasone C., Il parlamento europeo e l’intervento delle associazioni italiane di interessi nelle procedure parlamentari, in P.L. Petrillo (ed.), Lobby Italia a Bruxelles. Come, dove quando. E perché, Sinergie, Roma 2012, pp. 37 ss.

Mattina L., I gruppi di interesse, Il Mulino 2010

Morlino L. (ed.), Costruire la democrazia. Gruppi e partiti in Italia, Il Mulino 1991

Morlino L., Changes for Democracies. Actors, Struttures, Process, Oxford University Press 2011

Oliver D., Regulating the Conduct of MPs’, in Political Studies, 3, 1997.

Oxford Universal Dictionary, Oxford University Press, 1973.

Petrillo P. L., Democrazie sotto pressione, Parlamenti e lobby nel diritto pubblico comparato, Giuffré, Milano, 2011.

Santonastaso D., La dinamica fenomenologica della democrazia comunitaria. Il deficit democratico delle istituzioni e della normazione dell’UE, Edizioni scientifiche italiane, Napoli, 2004.

Thomas C. S., Political Parties and Interest Group: Sharing Democratic Governance, Boudler, Linne Rienner, 2001.

Truman D., The Governmental Process: Political Interests and Public Opinion, Knopf, New York, 1951.